Photo Trouvée, memory as an art form

Anyone who loves those anonymous images that the French call photographie trouvée or photographie anonyme, vintage finds that epitomize the word “snapshot”, never really stops looking for them. There is an ever-present sense of anticipation and longing because they are literally anywhere, hiding in plain sight all over the world.

They not only tell our stories; they become who we are. They capture everyday existence as well as special occasions, our great loves and tender embraces, kids at play, simple street scenes, even our flaws and foibles. Today more than ever, collectors are doggedly seeking these imperfect and at times distorted images, the kind that foreshadow, complement and advance the visual innovations of the twentieth-century avant-garde. With such widespread access to the technology since the turn of the last century, photography has become part of the collective consciousness – as a way of seeing the world, as an art form, as a means of memory-making – and changed our lives forever with scores of anonymous, poetic and mysterious little masterpieces.

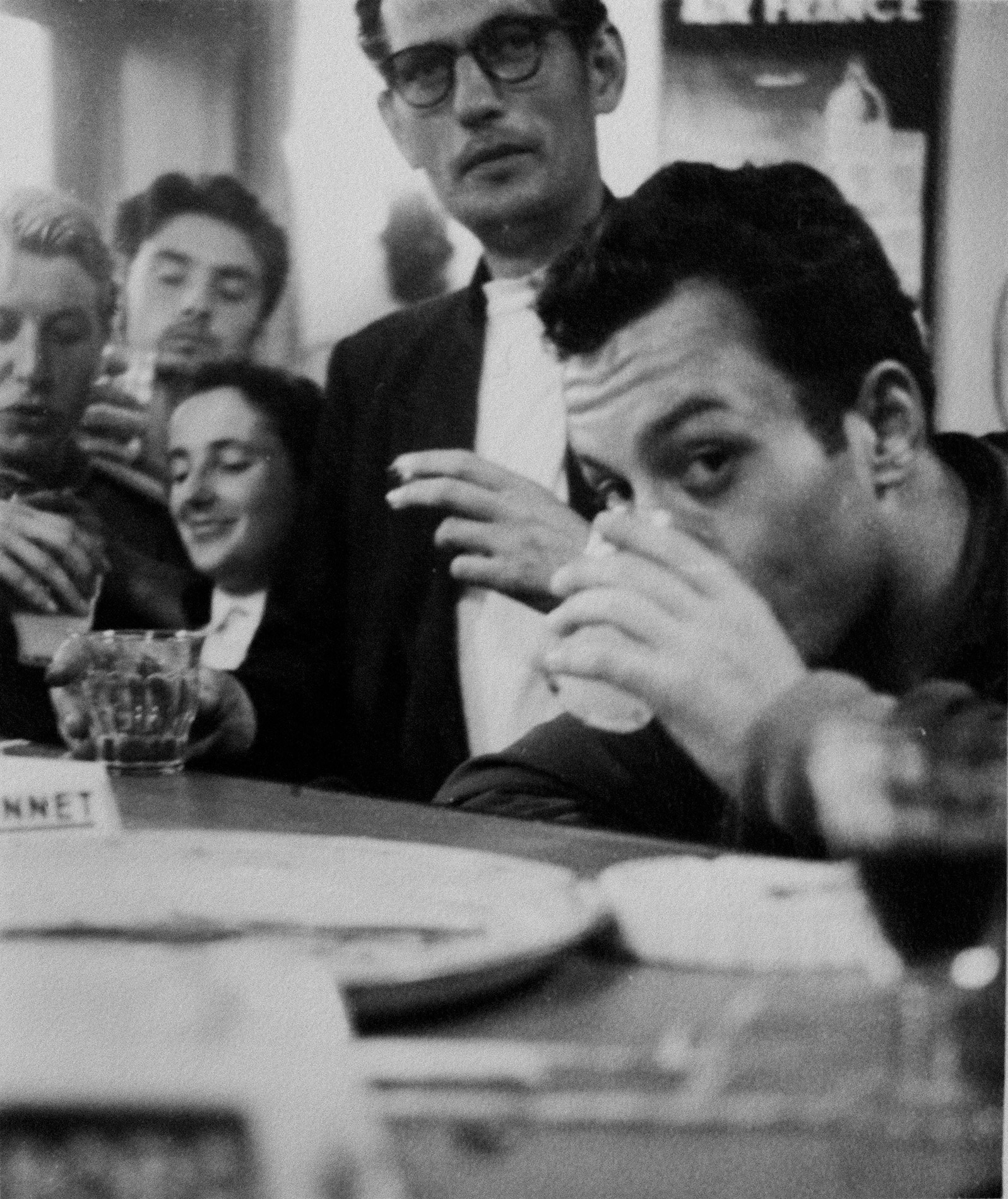

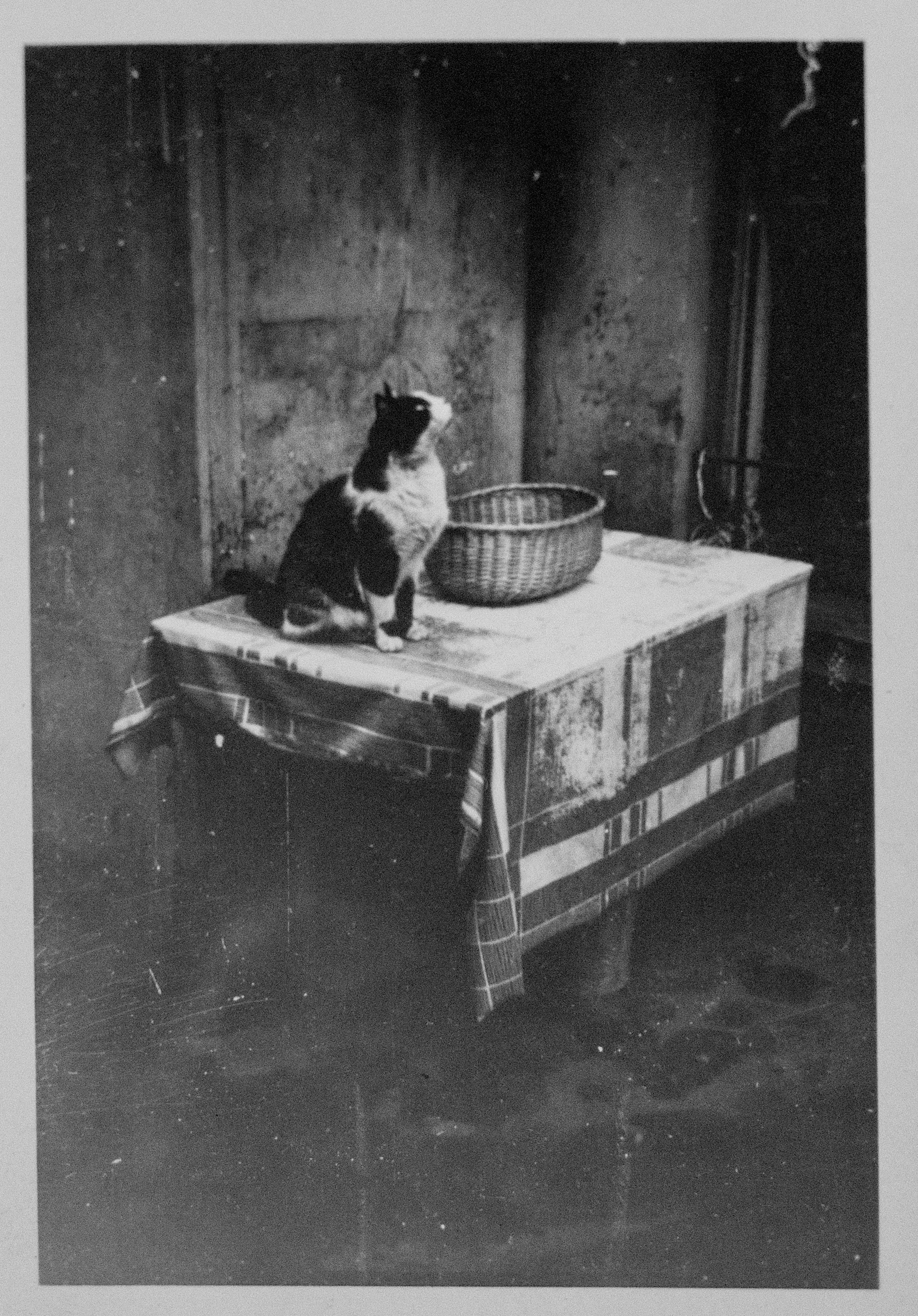

More than a decade ago, Valentina De Santis, CEO and owner of Grand Hotel Tremezzo and Passalacqua, became fascinated with “other pictures” and started her own collection, focusing on a subject close to her heart, namely the pleasures of the table, of conviviality, so quintessentially Italian, such an authentic expression of culture the world over. She has found dozens and dozens of images in the course of her travels that compose a universe of flavors, objects, gestures and sentiments, some of which grace the large wall in Grand Hotel Tremezzo’s L’Escale restaurant.

Institutions as prestigious as the Museum of Modern Art or the Metropolitan Museum in New York have recognized the impact of this seemingly limitless supply and started to include found photographs in their collections. The more receptive the art world became toward photos trouvées, the more this new movement spread worldwide, from America into Europe where the French raised the art form to new heights – unsurprisingly, it was the Surrealists who first saw the hidden beauty in the anonymous as the most accurate expression of the subconscious. Scholars and collectors have since achieved renown: Clément Chéroux, a historian of photography and now Chief Curator of Photography at MoMA, as well as Cédric de Veigy, Robert E. Jackson, Michel Frizot, Sébastien Lifshitz and above all Thomas Walther, who coined another very evocative term for this extraordinary material: the other picture.

We have a great many ways and reasons to gather around a table, it seems, as we see in a recent article featuring Valentina’s collection in the Italian edition of How To Spend It published by Italy’s financial newspaper of record Il Sole 24 Ore. They may capture an elegant picnic on a white tablecloth in late 19th-century France; a female soldier during the First World War, perhaps on leave, posing with a plate of pasta; two brothers sharing a bottle of wine; a dinner with thirty or more guests gathering for some special occasion, an anniversary perhaps; or a latter-day still life on a bistro table with a cup of coffee, a pack of cigarettes, a slice of bread and some coins.

“What has always fascinated me about these images,” says Valentina De Santis, “is how they are at once resilient and fragile. So small and so intimate that you can hold them in your hand, yet so timeless that they strike us as fresh and alive a century after they were taken. I discovered my first photo trouvée by chance at a flea market in Paris and have been collecting them for years with the same passion as that day. It excites me every time I find one of these little time capsules, a memory that endures on paper alone. I love to linger on the faces, the smiles, because everyone always smiles around the dinner table. Hardly any other place has the same energy, the same warmth, the same delicious smells able to raise our spirits, relax us and bring us closer together. This is what originally inspired my collection. And it has me wondering whether the photos we take every day and post on social media will ever have the same power. Will anyone ever go to the trouble of ‘finding’ them in a hundred years?” Who, pray tell, will keep our memories alive?